gay disease homosexual plague

gay disease homosexual plague

Exploring the Rhetorical Choices That Defined the 2022 “Mpox” (Monkeypox) Outbreak

George Washington University | School of Media & Public Affairs | Tuesday, May 2, 2023

Sarah Jester

-

What rhetorical choices were made by elites and the public to discuss the mpox outbreak?

-

What rhetorical strategies can be implemented by the government and public health experts to discuss emerging pandemics and epidemics that prioritize harm reduction for marginalized populations?

Research Questions

war on deviance

war on deviance

Literature Review

-

Members of the public require informational shortcuts to understand complex ideas. While the National Library of Medicine may refer to COVID-19 in a communication directed to subject matter experts as “prone to genetic evolution with the development of mutations over time, resulting in mutant variants that may have different characteristics than its ancestral strains,” a communication from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) tells the general public to “think about a virus like a tree growing and branching out, [where] each branch on the tree is slightly different than the others” when explaining COVID-19 variants.

Here, the CDC employs a common rhetorical strategy by including metaphors in their public health communications. A metaphor is a figure of speech intended to represent or reference a separate phenomenon (Merriam Webster). In political and public health contexts, metaphors are frequently used to convey complicated information to the public. When used responsibly, metaphors pinpoint the most salient and urgent aspects of a situation and place them in the context of a commonly understood frame of reference. Successful metaphors identify a problem and a course of action to resolve said problem. A set of metaphors used to describe one phenomenon can be incorporated into an overarching metaphorical framework, through which a speaker can compare and describe different aspects of a situation by referencing a more commonly understood framework. For example, the last three years have constituted a “War on COVID-19” in America, where masks and vaccinations acted as weapons against the enemy virus.

Despite the benefits of this rhetorical strategy, employing metaphors as informational shortcuts in the context of infectious diseases can cause harm. Overgeneralizing incredibly complex viruses in emergency situations runs the risk of misdirecting and confusing the public. When misused, metaphors can alienate and endanger marginalized populations that disproportionately suffer from the disease, designating infected individuals as the problem rather than the disease itself.

Many studies have correctly noted that it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between the use of certain metaphors and acts of racism or discrimination. Current research suggests that establishing a link between a social group and a disease will “activate” discriminatory sentiments in the public (Reny & Barreto). Several researchers have coined the term “disgust sensitivity” to explain the scientific connection between targeted metaphors and resulting xenophobia. This refers to the behavioral immune system’s practice of scanning an environment for harmful pathogens, using disgust as a tool to keep harmful people or objects away from the body (Reny & Barreto). Disgust sensitivity has since been found to be a strong predictor of xenophobia and discrimination in public health contexts (Reny & Barreto).

****

“Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19).” National Institute of Health.

“Metaphor Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster.

Reny, Tyler, and Matt Barreto. “Xenophobia in the Time of Pandemic: Othering, Anti-Asian Attitudes, and Covid-19.”

Variants of the Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022.

-

War metaphors are phrases that evoke imagery of battles, fights, or high-stakes competition. Clear-cut winners and losers are created through these metaphors – there are no stalemates in war (Sontag, Susan). Terms like “defeating ‘x’,” “fighting ‘x’,” or “the war on ‘x’” are typical of war metaphors. In the context of a virus, war metaphors should theoretically paint the disease as the enemy of the people. Once the disease is eradicated, the war is won and survivors emerge victorious.

War metaphors populate our daily remarks and conversations, but also constitute larger frameworks that are used to shape perspectives on a particular issue. The War on Drugs, the War on Terror, and the War on Poverty were each declared by political administrations to encompass policies and actions taken to combat societal issues. Diseases are no exception here — the War on COVID-19 is fresh in America’s memory.

The use of war metaphors to describe diseases dates back to the birth of public health discourse. Medical professionals in the early 1900s trying to protect the public from tuberculosis produced illustrated flyers with flies and pests depicted as enemy aircrafts dropping bombs labeled “microbes” and “illness” (Sontag). Other flyers advised the public to fight back against the “enemy” with an arsenal of “weapons,” or illustrated swords labeled as “cleanliness,” “rest,” and “hygiene” (Sontag).

Why do political and public health institutions alike have such a long history of using war metaphors to describe epidemics? Hillmer writes that “since an illness includes innumerable chemical processes inside the body which cannot directly be seen, we use the source domain of war to make those processes easier to understand” (Hillmer). Although individuals might not fully grasp the medical terminology or urgency related to a disease, the concepts of enemies, battlegrounds, weapons, defenses, victories, and defeats are nearly universal (Lakoff and Johnson).

Despite their frequent use in what should be an apolitical issue, war metaphors are inherently political. Wars are not won without casualties. Victimhood in war is purely political – civilian casualties are mourned by whole nations; prisoners of war are captured by the enemy side and succumb to their fate. Susan Sontag writes that “victims suggest innocence - innocence [in turn] … suggests guilt” (Sontag). Implications of innocence and guilt become dangerous in epidemics. To imply that an unassuming person is somehow at fault for falling ill is harmful and perpetuates any existing misconceptions about that person’s identity. Put simply, war metaphors can stigmatize infected individuals, whether or not the speaker intends for this to occur (Sontag). Politicizing epidemics can also mislead the public into believing that diseases are concentrated partisan issues rather than a nondiscriminating medical phenomenon (Power, Jennifer).

America is no stranger to declaring unsuccessful wars on grand, overarching problems. “If a virus is an enemy, it’s an enemy without generals, a foe with no military training academy, an adversary with no master plan for world domination,” writes author and journalist Moustafa Bayoumi. “The lack of structure within the war metaphor allows far too much room for misinterpretation of who the enemy is, who the victorious side might be, and who should be blamed for any lasting conflict after ‘victory’ is declared” (Bayoumi, Moustafa). The respective Wars on Poverty, Drugs, and Terror have all failed at achieving their objectives. Yet, they each succeeded in misdirecting public vitriol towards impoverished communities and people of color (Bayoumi). War is senseless and leaves violence, trauma, and death in its wake. With no room for marginalized communities to obtain equal footing in battle, America’s wars cause innocent casualties rather than alleviating root problems.

****

Bayoumi, Moustafa. “The Coronavirus and the Failures of War Metaphors.” Moustafa Bayoumi, 12 Apr. 2020.

Hillmer, I. (2007). The way we think about diseases: “The immune defense” - comparing illness to war. NAWA J. Lang. Commun. 1, 22–30.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press, 1981

Sontag, Susan. AIDS and Its Metaphors. Penguin, 1988.

“The ‘Homosexual Cancer’: AIDS = Gay.” Movement, Knowledge, Emotion: Gay Activism and HIV/AIDS in Australia, by Jennifer Power, ANU Press, 2011, pp. 31–58.

-

Disease metaphors are phrases that evoke imagery of serious illnesses. Disease metaphors frequently employ the words “cancer” or “plague” to refer to their subject matter (Sontag). The term “plague” is one of the most prolific disease metaphors used to describe large-scale epidemics throughout history, whether or not they actually resemble plague-like proportions. The term “plague” consistently evokes the highest levels of chaos, evil, and destruction in the public consciousness as compared to other disease metaphors (Sontag).

Kathleen Hines uses a disease metaphor of her own to share that “plague’s slippery meaning in language is a symptom of its contagion” (Hines, Kathleen). The biblical origins of plague terminology specify that plagues are not caught by just anyone – they are a judgment on society from God himself, inflicted as punishment for deviance (Sontag). Similar to war metaphors, disease metaphors imply that infected individuals are deserving of illness and death as a result of their lifestyle and background.

The magnifying glass that is placed on at-risk populations through disease metaphors is further sharpened through “the need to make a dreaded disease foreign” (Sontag). Diseases are frequently described as foreign plagues and deadly illnesses hailing from faraway lands. This type of rhetoric has the potential to evoke xenophobia and all sorts of hateful and discriminatory sentiments in an audience. The natural progression of the plague metaphor is to place the blame on “foreigners” for the illness (Sontag). Sontag writes that the plague metaphor “brings summary judgments about social crisis and impacts political response” in a given setting (Sontag). In the same way that war metaphors position audiences into an “us vs. them” mindset, disease metaphors fashion the population into two segments: innocent survivors and infected individuals that ultimately deserve their fate.

****

Hines, Kathleen. “Contagious Metaphors: Liturgies of Early Modern Plague.” The Comparatist, vol. 42, University of North Carolina Press, 2018, pp. 318–30.

Sontag, Susan. AIDS and Its Metaphors. Penguin, 1988.

-

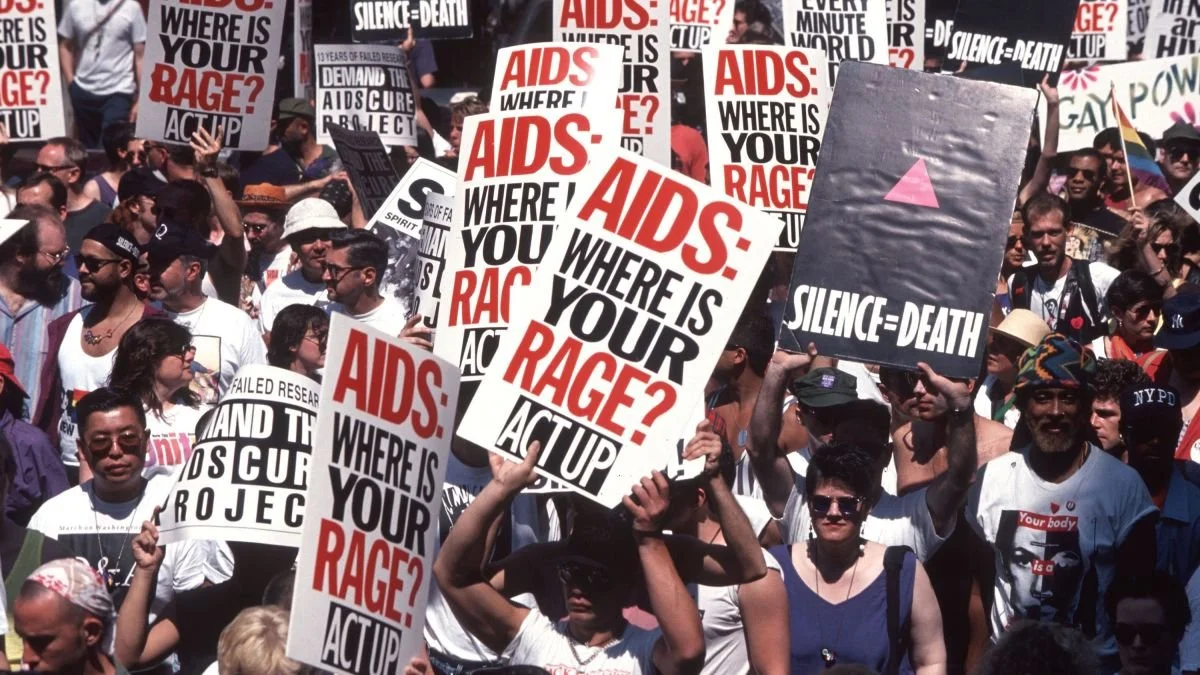

Susan Sontag is credited with developing one of the first comprehensive frameworks that examines the effects of metaphors used to discuss infectious diseases. Sontag famously analyzed the metaphors disseminated during the AIDS epidemic, criticizing the news media and the Reagan administration’s harmful use of war and disease metaphors throughout the crisis. She argues that due to the intrinsically political nature of war and disease metaphors, the public discourse about AIDS encouraged homophobia and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ community rather than illuminating any preventative measures or the pursuit of a cure (Sontag).

Throughout the 1980s, AIDS was largely perceived as a disease that only impacted gay men, an already stigmatized population. The use of popular war metaphors like “the AIDS invasion,” “the war on AIDS,” and “battling AIDS” only further stigmatized gay men (Sontag). AIDS was frequently described by a multitude of political actors and media outlets as a type of “enemy invasion.” In such an invasion, the body’s cells “mobilized” to attack the immune system of infected individuals. AIDS was depicted as not only invading the body of infected individuals, but invading society at large. Sontag suggests that gay men in America were perceived as being the sole carriers of AIDS, thus acting as deviant “invaders” of an otherwise pure society – much as the disease invaded immune systems (Sontag). We can conclude that the association between homosexuality and deviance was further strengthened by the dissemination of war metaphors throughout the 1980s, which led to increased stigmatization and criminalization of gay men.

As for disease metaphors, terms like “the gay plague,” “the homosexual cancer,” or “the homosexual plague” flourished at the height of the epidemic (Sontag). As disease metaphors continued to dominate political discourse and news headlines around the nation, attitudes of homophobia steadily increased (Ruel and Campbell). Cruel jokes were frequently made by members of the Reagan administration at the expense of gay men. At a packed briefing, White House press secretary Larry Speakes publicly subjected a journalist to comments about his sexual orientation - on the record - when he questioned how the president was addressing the AIDS epidemic, eliciting a round of laughter from the room (Ruel and Campbell). By inextricably linking AIDS to themes of homosexuality, deviance, and sin through the use of disease metaphors, political actors and media outlets discouraged meaningful medical action against the disease.

****

Ruel, Erin, and Richard T. Campbell. “Homophobia and HIV/AIDS: Attitude Change in the Face of an Epidemic.” Social Forces, vol. 84, no. 4, 2006, pp. 2167–2178. JSTOR.

Sontag, Susan. AIDS and Its Metaphors. Penguin, 1988.

-

The use of anti-Asian disease metaphors stretches back many centuries. When Chinese laborers first arrived in America in the early 1800s, the term “Yellow Peril” catapulted into the public consciousness, describing an intense period of irrational fear of Asians (Rubin, Daniel). Chinese immigrants have long since been stereotyped as carriers of disease, with Americans in the late 1800s concluding that Chinese people, “bred and disseminated disease, thereby endangering the welfare of the state and the nation” (Reny and Barreto).

The same framing patterns observed during the Yellow Peril and at the peak of the AIDS epidemic have resurfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contemporary anti-Asian disease metaphors have invoked Yellow Peril imagery and endangered the safety of Asian Americans as a result. Traditional news media outlets fell prey to this practice at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic – a New York Times reporter writing about the disease described it as “a deadly Chinese coronavirus” in January of 2020, closely followed by a Wall Street Journal article referring to China as “the real sick man of Asia” during that time period (Rubin).

During the earliest months of the pandemic, President Trump and other members of his administration frequently used disease metaphors like the “China virus,” “Wuhan virus,” and “Kung Flu” to describe COVID-19 (Dhanani and Franz). This type of rhetoric had a direct impact on the safety of people of East Asian descent in the Western world (Dhanani and Franz). One study found that respondents with less accurate knowledge about COVID-19, coupled with increased trust in President Trump, were more likely to report negative attitudes and likelihood to engage in discriminatory behavior towards Asian Americans (Dhanani and Franz). One third of Asian Americans surveyed reported that they had been targeted with racist slurs, jokes, and acts of violence following the start of the pandemic. Researchers concluded that trust in President Trump increased the likelihood of being exposed to anti-Asian disease metaphors, in turn increasing the likelihood of acts of racism and discrimination occurring against Asian Americans (Dhanani and Franz).

The beginning of the pandemic was largely dominated by the aforementioned disease metaphors, with war rhetoric failing to enter the picture until April of 2020. That month, President Trump “declared war” on COVID-19, saying, “I view it—in a sense as a wartime president” (Sered, Susan). “We’re at war with the virus,” proclaimed Joe Biden during his presidential run (Sered). “This is a war,” Andrew Cuomo concurred (Sered). These declarations prompted a wide range of responses from communications scholars, with many pointing out the negative ramifications of this metaphor. “Like any war, COVID-19 will disproportionately hurt those who are already vulnerable,” wrote author and sociology professor Susan Sered. “Metaphorical wars on disease easily turn into wars on those who are believed to embody the disease, as was the case in the early decades of the HIV/AIDS epidemic” (Sered).

Despite having slowed over the last year, the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing. With new scientific developments coming to light, the manner in which the pandemic is discussed by political actors, the media, and the public will continue to shift. However, it is telling that two presidents on different sides of the aisle relied on variations of disease and war metaphors to guide public thought and actions relating to the pandemic, as did the Reagan administration at the height of the AIDS crisis.

****

Dhanani, L.Y., Franz, B. “Unexpected public health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey examining anti-Asian attitudes in the USA.” Int J Public Health 65, 747–754 (2020).

Reny, Tyler, and Matt Barreto. “Xenophobia in the Time of Pandemic: Othering, Anti-Asian Attitudes, and Covid-19.” Taylor & Francis, Apr. 2020.

Rubin, Daniel. A Time of Covidiocy: Media, Politics, and Social Upheaval. Brill, 2021.

Sered, Susan. “Why 'Waging War' on Coronavirus Is a Dangerous Metaphor.”

-

The monkeypox virus – hereafter referred to as “mpox” – is a “viral zoonosis, [or] a virus transmitted to humans from animals” with symptoms resembling those of smallpox (World Health Organization). With the first recorded human case occurring in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970, mpox is most common in areas close to tropical rainforests in central & west Africa, although the virus has recently cropped up in urban areas across the world (World Health Organization).

The most visible and common symptom of mpox is a rash that may develop on an individual’s hands, feet, face, chest, mouth, or genitals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Mpox rashes can be itchy, painful, and initially appear as pimples or blisters before scabbing over a period of several days or weeks. Infected people may also experience flu-like symptoms like fever, chills, fatigue, or respiratory symptoms (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Human transmission of mpox occurs through close skin-to-skin contact, including direct contact with mpox rashes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Mpox can be spread through both sexual and non-sexual contact, through birth, and from contact with infected animals. Scientific research to determine if the virus spreads through respiratory secretions and genital fluids, and how the virus spreads when symptoms are not yet present, is ongoing (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

****

“How It Spreads.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 Feb. 2023.

“Monkeypox.” World Health Organization, 2022.

“Signs and Symptoms.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 Feb. 2023.

-

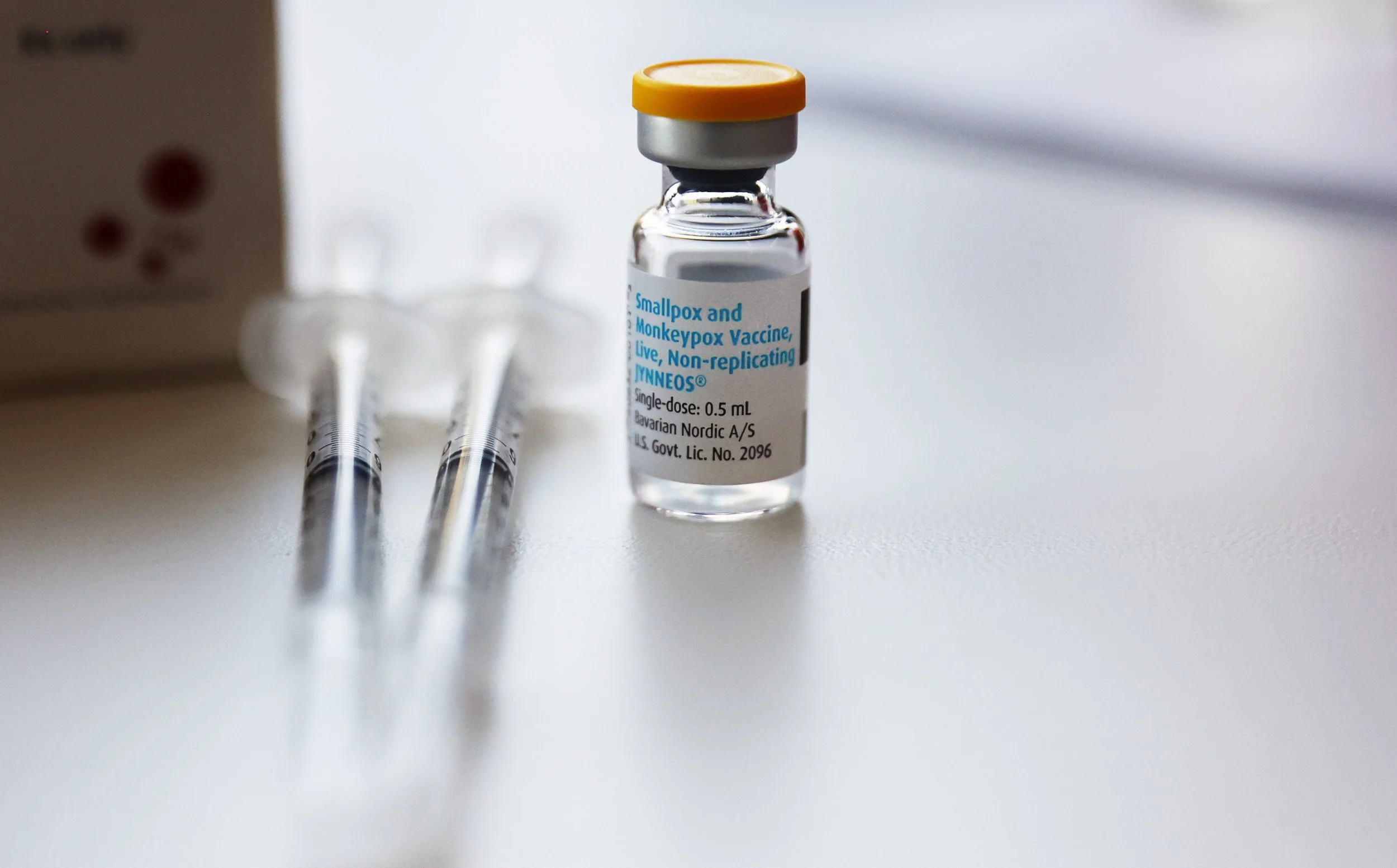

The non-endemic mpox outbreak of 2022 began on May 7, 2022 in the United Kingdom, where a patient was treated for mpox after returning from a trip to Nigeria. The following week, under 100 confirmed and suspected cases combined were reported in Canada, Italy, Portugal, and the United Kingdom (Think Global Health).

With mpox continuing to spread throughout non-endemic nations, LGBTQ+ activists called for more attention and resources to be devoted to the prevention of mpox, and for acts of homophobia against gay men to be condemned. In late July 2022, WHO reversed its previous decision and officially labeled mpox as an international public health emergency, “a designation used to describe only two other diseases, COVID-19 and Polio…[opening] the door for a coordinated international response to fight the virus” (Think Global Health).

In early August 2022, WHO began soliciting suggestions from the public to rename the “monkeypox” virus. In November 2022, after most affected nations had successfully accessed and implemented vaccination and treatment programs, WHO recommended a new name for the virus: “mpox” (Think Global Health). As mpox management officials transitioned out of the White House into the CDC, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a 60-day expiry notice for the public health emergency declaration issued in August, with the Biden administration not planning to renew the declaration in 2023 (Nirappil, Fenit). As of February 15, 2023, there have been 30,193 recorded cases of mpox in the United States from the 2022 outbreak. In 2022, there were 32 confirmed U.S. deaths from mpox. Globally, there have been 85,922 mpox cases recorded during the 2022 outbreak (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

****

“2022 Outbreak Cases and Data.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 31 Jan. 2023.

“Monkeypox Timeline.” Think Global Health, Council on Foreign Relations, Jan. 2023.

Nirappil, Fenit. “Biden Administration Poised to Lift Monkeypox Emergency Declaration.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 2 Dec. 2022.

-

Monkeypox was given its original name in 1970 when it was discovered in captive monkeys – although the virus itself did not originate in monkeys (Gumbrecht, Jamie). Following the spread of the virus to non-endemic countries in 2022, scientists and rhetoric experts raised concerns about the negative impact that the name of the virus could have on the willingness of the general public to get tested or vaccinated. Additional levels of stigmatization were added with gay men of color being the primary population at risk for catching the virus (Gumbrecht, Jamie). In a letter to WHO, New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Ashwin Vasan wrote that there was “growing concern for the potentially devastating and stigmatizing effects that the messaging around the ‘monkeypox’ virus can have on these already vulnerable communities” (Gumbrecht, Jamie).

Under the stipulations laid out by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), WHO has the authority and responsibility to assign names to new diseases. In very rare cases, WHO may rename existing diseases if certain conditions are present (World Health Organization). On November 28, 2022, WHO issued a news release discussing their decision to implement the term “mpox” rather than “monkeypox” to describe the virus outbreak. The official release explained that following the mpox outbreak in May 2022, a number of instances of “racist and stigmatizing language online, in other settings and in some communities was observed and reported to WHO” (World Health Organization).

****

Gumbrecht, Jamie. “Who Renames Monkeypox as 'Mpox'.” CNN, Cable News Network, 28 Nov. 2022.

“International Classification of Diseases (ICD).” World Health Organization.

“WHO Recommends New Name for Monkeypox Disease.” World Health Organization, 2022.

History has repeated itself with the mpox outbreak. So have harmful rhetorical patterns that were used during the AIDS epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic.

Rhetorical Timeline

Warning: Sensitive Content

-

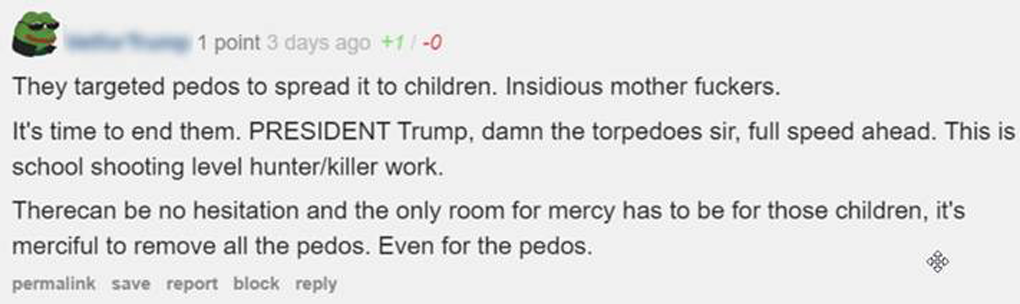

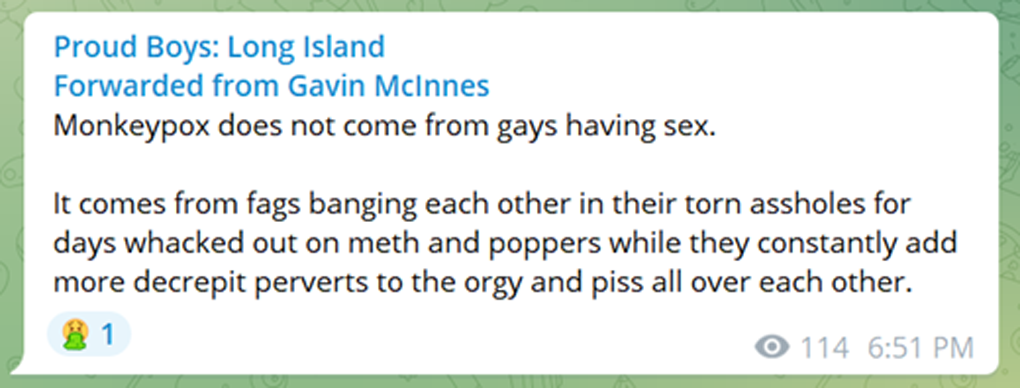

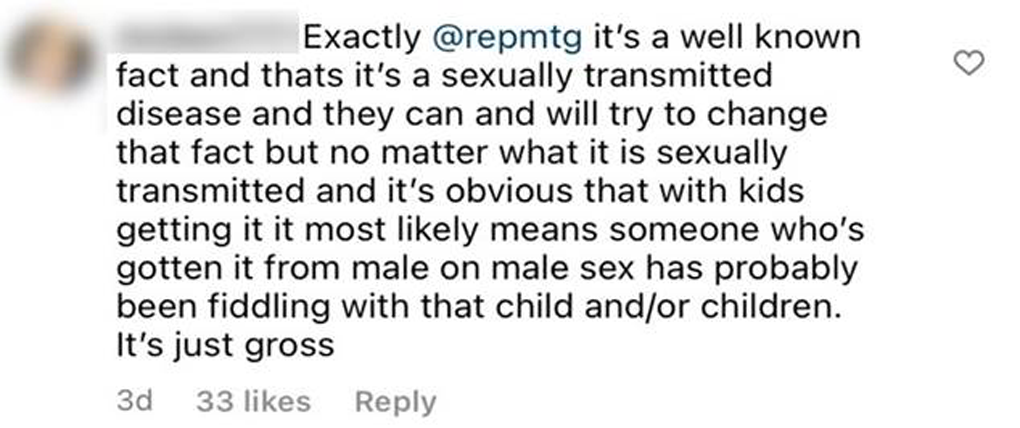

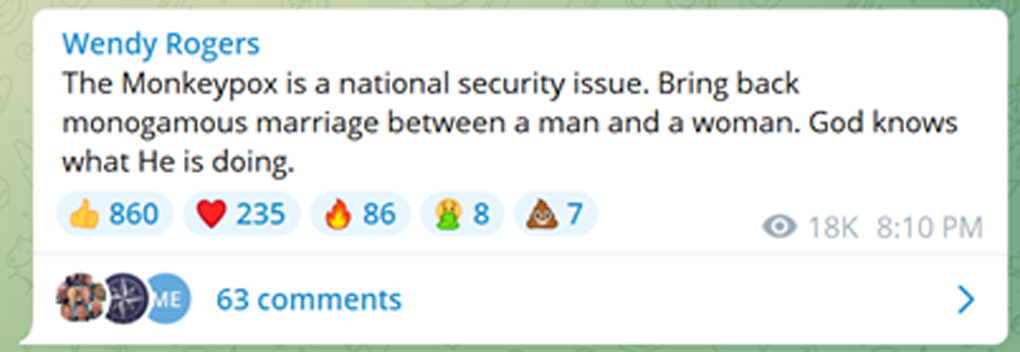

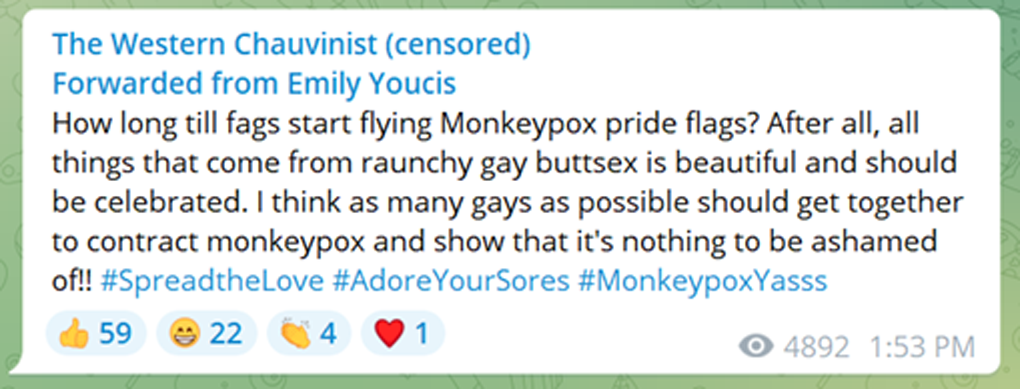

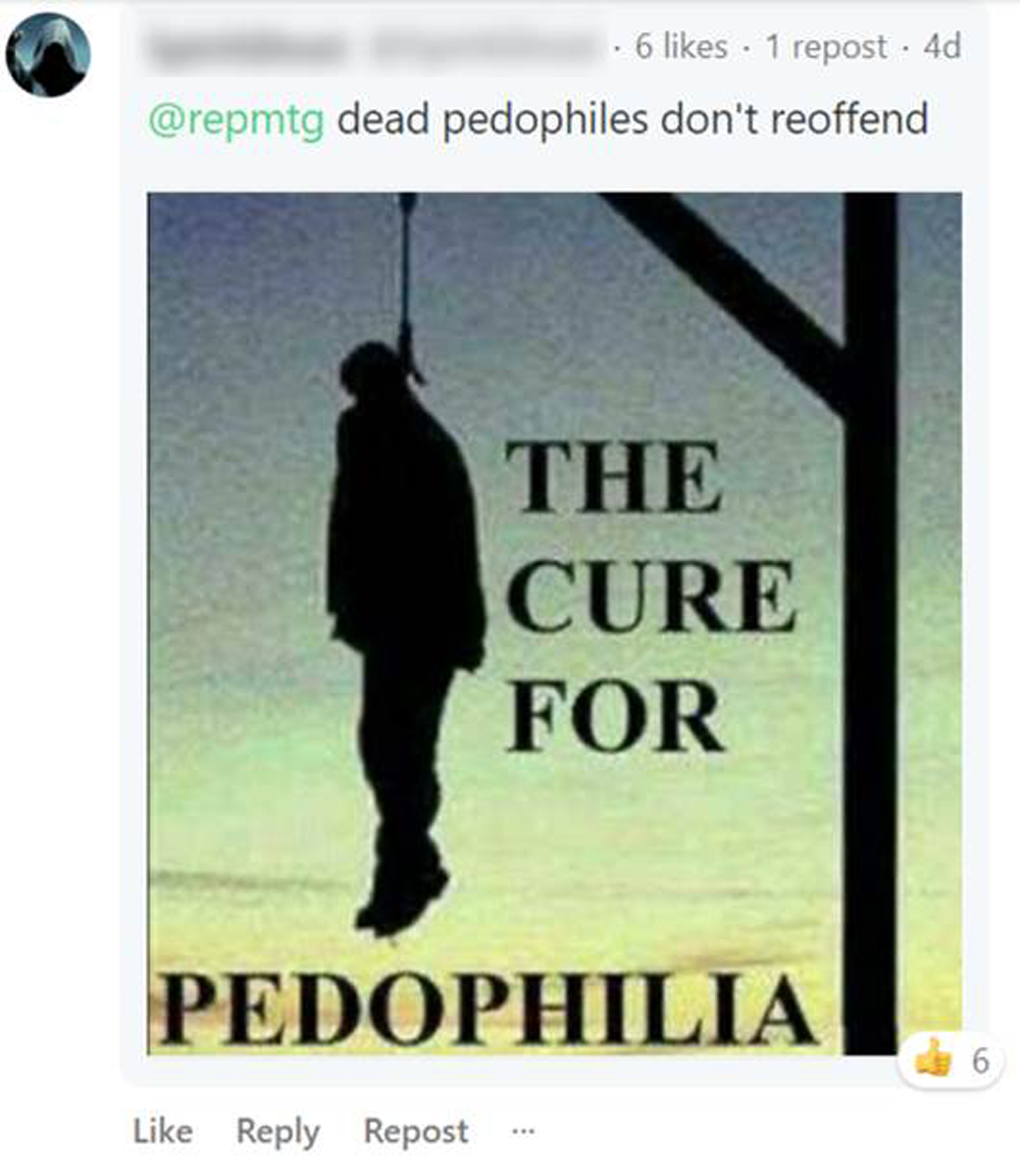

Public health experts have noted that as the virus spread, so too did instances of discrimination against gay men and communities of color (Chappell, Bill). In August, The Guardian shared, “On TV, rightwing commentators openly mock monkeypox victims – the vast majority of whom are men who have sex with men – and blame them for getting the disease” (Chan, Wilfred). The “aggressive stigmatization” of monkeypox and the LGBTQ+ community through attacks by right-wing media and online citizens alike follows the rhetorical AIDS playbook outlined by Sontag decades ago, with metaphors like “gay disease” and “gay virus” resurfacing (Sontag).

****

Chan, Wilfred. “Rightwing Media Embraces AIDS-Era Homophobia in Monkeypox Coverage.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 10 Aug. 2022.

Chappell, Bill. “Who Renames Monkeypox as Mpox, Citing Racist Stigma.” NPR, National Public Radio, 28 Nov. 2022.

-

To construct a digital timeline of the non-endemic mpox outbreak, I examined mpox news coverage that was published between May 2022 to December 2022 to determine key developments in chronological order.

For the purposes of identifying rhetorical patterns in mpox discourse similar to those used during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and AIDS epidemic, I utilized the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD)’s comprehensive analysis of trending phrases on Twitter related to mpox. I then conducted advanced searches on Twitter for each month between May 2022 and December 2022 with the following presets:

Tweets in the specified timeframe must include the term “monkeypox” and may include any of the following terms: “groomer pedo pedophile lgbt rape molester queer fag faggot”

The second set of terms are among the most frequently used words included in tweets that discuss mpox and employ anti-LGBTQ perspectives. Many tweets that matched this search criteria have been removed from Twitter for hate speech or disrespectful conduct. The tweets included in the rhetorical timeline below have not yet been removed and have the highest engagement and/or popularity rates out of all those that match the search criteria in the specified timeline.

-

I used tweets as the primary basis for this rhetorical analysis as news coverage in 2022 labeled Twitter as one of the social platforms most susceptible to misinformation, disinformation, and homophobic attitudes regarding mpox. Since social platforms like Facebook and Instagram took swifter action to remove and combat disinformation, with many homophobic and misleading posts being deleted altogether, they were not included in this analysis. For the month of July 2022, posts from the popular right-wing social network Telegram have been included to account for the significant spike in anti-LGBTQ mpox discourse on the platform following Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene’s tweet regarding mpox late that month.

The months of September & October and November & December have been consolidated into two sections instead of four to account for the significant decrease of mpox cases in fall of 2022, as well as the decision of White House officials not to renew the public health emergency designation in place for the virus.

Scroll down to explore an interactive digital timeline of the 2022 mpox outbreak and rhetorical patterns that were used by members of the public and government officials alike to describe the virus.

May 2022

Translation: 20 years ago, homosexuality was criminalized in all international laws and laws, but within a few years, the homosexual lobby managed to change the laws and become one of the strongest, most shameless and influential lobbies in the world, and because what is going on is a war against God, the laws of God intervene by afflicting them with deadly diseases and pains, the last of which is #جدري_القرود

June 2022

July 2022

August 2022

September & October 2022

November & December 2022

Present Day: 2023

Mpox may not appear as frequently in American news coverage in the present day, but the rhetorical patterns we observed on social media in 2022 have continued into 2023. Nearly a full year after the start of the non-endemic outbreak, what are people saying online about mpox today?

groomer pedophile gay disease

groomer pedophile gay disease

Discussion

How did these harmful frames spread? And how did the proliferation of this type of rhetoric impact the LGBTQ community? These two considerations are essential in determining a rhetorical path forward that prioritizes harm reduction for marginalized communities amidst epidemics.

Robert Entman’s original cascading network activation & framing model posited that presidential administrations and other members of the executive branch originally occupied the most powerful section in a top-down flow of communication. These individuals would communicate key messages and frames to non-administration elites like Congress members, experts, and lobbyists, who in turn passed messages and frames along to the institutionalized mainstream media. From there, members of the media would instill or activate these frames in members of the public through news texts in which key issues and messages were printed. In simpler terms, frames were created and activated through a “top to bottom flow with networks of association linking ideas, symbols, and people.”

Entman’s original model best describes the dissemination of war and disease metaphors during the AIDS epidemic by the Reagan administration. However, the introduction of new technologies and social platforms has effectively disrupted the legacy structure in place. In 2018, Nikki Usher and Entman proposed an update to the original model to better describe and understand framing processes “in a fractured democracy.” The updated model of cascading network activation has allowances for the partial nature of social platforms, as well as the tendency of algorithms to introduce bias into feeds and influence frame distribution for users.

Through Entman’s updated model of cascading network activation, social media platforms now have the ability to intervene between members of the public and the institutional news media. Whereas the news media formerly served as the main point of connection between elites and the public, elites now have the ability to bypass the mainstream media and speak directly to the public through platforms like Twitter and Facebook. Elites do not have to rely solely on frames distributed by the news media and can introduce their own perspectives directly to highly polarized audiences. Conversely, citizens can engage each other directly on social media platforms, which was not easily facilitated prior to the advent of the Internet.

The cascading network activation model is especially salient within the conservative media subsystem. Entman and Usher write that the “conservative subsystem enforces tighter connections among elites, media, and publics than the less commercially successful liberal subsystem.” Social media algorithms increase the distribution of certain frames depending on their performance in different user feeds. As a result, right-wing users who engage with a certain type of frame will see more of that frame in their feeds. Finally, “dysfunctional government feeds public anger, communication networks polarize further, and democracy enters a downward spiral.”

It is through this model that disease metaphors proliferated and thrived online during the mpox outbreak of 2022. The highest performing tweets included in the mpox rhetorical timeline mainly come from verified Twitter accounts and public figures with large audiences. In July, right-wing congressional elites like Marjorie Taylor Greene and Wendy Rogers each shared messages with their social audiences that likened gay men to pedophiles and rapists, and the mpox outbreak itself to an act of God. These frames are by no means original — nearly identical ones were distributed during the AIDS epidemic. However, through the infinite reach offered by social media platforms, these homophobic frames were captured and replicated tenfold by members of the public, with far right-wing outlets mirroring some of their characteristics in news coverage.

With a base understanding of how harmful rhetoric spread during the mpox outbreak, we can more deeply comprehend how the frames that were used impacted the LGBTQ community. The failure of the news media and elites on all sides of the aisle to frame the virus as a nondiscriminating illness that anyone could catch resulted in increased attitudes of homophobia online and offline. In August of 2022, one week after the White House declared mpox a public emergency, two gay men were attacked in Washington, DC by assailants that used homophobic slurs and referenced mpox. Hate crimes do not occur in a vacuum — they are encouraged by frames like those listed in the rhetorical timeline above.

act of god

act of god

Where do we go from here? How can public health experts and government officials practice rhetorical harm reduction when discussing epidemics and viruses?

Metaphorical Repository

-

Natural disaster metaphors, disaster preparedness metaphors, and storm metaphors are typical in discourse surrounding financial and business crises. During the financial crisis of 2008, wind, storm, and water metaphors were among the most frequent frames used by journalists to describe economic downturn. Phrases like “financial storm,” “vortex of ruin,” “commercial earthquake,” and “financial meltdown” were popularized at this time and are still visible in financial discourse today.

Storm and natural disaster metaphors can be organized into two categories - the crisis approach and the recurring crisis approach. Under the crisis approach, problems occur accidentally. The recurring crisis approach stipulates that storms have a more predictable nature based on environmental factors. Within the singular crisis approach, speakers cannot place blame on any one person or group for a storm or natural disaster, allowing policymakers to turn the attention of the public to solutions rather than the origins of the crisis.

-

Key parameters for the natural disaster framework focus on the types of storms that are included. Hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, severe rainstorms, and earthquakes are all destructive natural disasters that are appropriate to use as parallels within this framework because they occur unprovoked and can cause significant damage. However, natural disasters like fires should be excluded from this framework. Fires can be started purposefully, or center an individual to blame, and grow over time. Furthermore, fires can be put out by firemen, whereas nothing can really be done to stop a hurricane, tornado, or earthquake in its tracks.

-

Natural disaster metaphors are not an incitement to violence. There are no ingroups and outgroups for natural disasters - they have the potential to affect everyone equally. Although America’s coasts are more vulnerable to certain types of storms, no one is truly immune from experiencing a natural disaster. No one group can be isolated as the “cause” for a storm, since these disasters occur naturally. Instead of creating an “us against them” dynamic that war and disease metaphors tend to evoke, the disaster preparedness framework creates a sense of “us against it,” with “it” referring to a natural disaster.

Although war metaphors encourage citizens to take up arms against an enemy, they do not account for the fact that most American wars take place on foreign soil, to which citizens are not usually firsthand witnesses. Natural disasters are bipartisan and occur every day within America’s borders, unlike wars. Families risk losing everything in a natural disaster, which is arguably a more urgent and compelling issue than a faraway war.

The natural disaster framework is well suited to public health rhetoric primarily because of the concept of social distancing. When natural disasters occur, local representatives often advise their constituents to stock up on supplies and stay indoors to avoid the worst of the storm. Ensuring that people stay inside or socially distance through a rhetorical approach that centers the natural disaster framework could help to significantly reduce the spread of cases across the nation amidst an epidemic or outbreak.

-

It is arguable that disaster and storm metaphors simply do not provide a strong enough call to action for citizens to protect themselves against disease. For many Americans, sheltering from a hurricane may not provide as much of an emotional appeal as taking up arms against enemy soldiers. The mental frames that natural disaster metaphors evoke may not be as salient as war metaphors, considering the favorability of war, battle, and the 2nd Amendment in the eyes of many American citizens. People that do not live near America’s coasts may have never experienced a natural disaster before.

The disgust sensitivity & fear of catching a virus that is evoked by disease metaphors may be a stronger motivator to quarantine or social distance than the idea of a hurricane or a tornado approaching. The disease metaphors that were conceived during the AIDS epidemic were proven to increase levels of disgust sensitivity in heterosexual Americans, which made them wary of catching the disease from gay men. Disaster metaphors have a much lower likelihood of activating disgust sensitivity. This is a positive outcome for the overall safety of marginalized populations, but could have a negative impact on how likely people are to mobilize to prevent the spread of mpox.

Demetre Daskalakis, White House National Monkeypox Response Deputy Coordinator, shared that the federal approach to discussing mpox was to use purely scientific language without incorporating many metaphors. It is too early to determine how successful this approach has been, but introducing a new metaphorical framework to discuss diseases, rather than relying on purely scientific language, may detract from the example that the White House set during the mpox outbreak.

-

Hurricanes

With [disease name] on the horizon, is your family prepared? We’re here to help you assemble a [disease name] preparedness toolkit, just like the emergency hurricane kit stored in your home.

[Disease name] can be frightening — but with the proper supplies and preparation, we can stand strong and stay safe in the face of the hurricane.

Severe Rainstorms and Tornadoes

We urge you to stay inside until this storm has passed - and the sun will rise again before you know it.

The hopeful thing about storms is that they pass - and by sheltering in place & socially distancing, we can stay safe until the sun comes out.

As [disease name] sweeps through the nation, remember that America has been weathered by many storms before. Like in all times of strife, we will protect each other until the tornado subsides and rebuild as one.

Earthquakes

When [disease name] strikes, it can feel like the ground beneath your feet is unsteady. Earthquakes can strike anywhere — and it’s important to be prepared.

Floods

[Disease name] is a flood that cannot always be stopped in its tracks - but we can take the necessary precautions to stay safe during the storm, and to rebuild our nation together once it has subsided.

shelter in place

shelter in place

Sources

“2022 Outbreak Cases and Data.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 31 Jan. 2023.

Bayoumi, Moustafa. “The Coronavirus and the Failures of War Metaphors.” Moustafa Bayoumi, 12 Apr. 2020.

Besomi, Daniele. “The Metaphors of Crises.” Taylor & Francis, Journal of Cultural Economy, July 2018.

Chappell, Bill. “Who Renames Monkeypox as Mpox, Citing Racist Stigma.” NPR, National Public Radio, 28 Nov. 2022.

Chan, Wilfred. “Rightwing Media Embraces AIDS-Era Homophobia in Monkeypox Coverage.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 10 Aug. 2022.

Dhanani, L.Y., Franz, B. “Unexpected public health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey examining anti-Asian attitudes in the USA.” Int J Public Health 65, 747–754 (2020).

Entman, Robert M, and Nikki Usher. “Framing in a Fractured Democracy: Impacts of Digital Technology on Ideology, Power and Cascading Network Activation.” Journal of Communication, vol. 68, no. 2, 2018, pp. 298–308.

“EPILOGUE: AIDS AND THE STATE ENMESHED.” Before AIDS: Gay Health Politics in the 1970s, by Katie Batza, University of Pennsylvania Press, PHILADELPHIA, 2018, pp. 130–136. JSTOR.

“Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19).” National Institute of Health.

Gumbrecht, Jamie. “Who Renames Monkeypox as 'Mpox'.” CNN, Cable News Network, 28 Nov. 2022.

Hillmer, I. (2007). The way we think about diseases: “The immune defense” - comparing illness to war. NAWA J. Lang. Commun. 1, 22–30.

Hines, Kathleen. “Contagious Metaphors: Liturgies of Early Modern Plague.” The Comparatist, vol. 42, University of North Carolina Press, 2018, pp. 318–30

Ho, Janet. "An earthquake or a category 4 financial storm? A corpus study of disaster metaphors in the media framing of the 2008 financial crisis." Text & Talk, vol. 39, no. 2, 2019, pp. 191-212.

“How It Spreads.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 Feb. 2023.

“International Classification of Diseases (ICD).” World Health Organization.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press, 1981.

“Metaphor Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster.

“Monkeypox.” World Health Organization, 2022.

“Monkeypox Timeline.” Think Global Health, Council on Foreign Relations, Jan. 2023.

Nirappil, Fenit. “Biden Administration Poised to Lift Monkeypox Emergency Declaration.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 2 Dec. 2022.

Reny, Tyler, and Matt Barreto. “Xenophobia in the Time of Pandemic: Othering, Anti-Asian Attitudes, and Covid-19.”

Rubin, Daniel. A Time of Covidiocy: Media, Politics, and Social Upheaval. Brill, 2021.

Ruel, Erin, and Richard T. Campbell. “Homophobia and HIV/AIDS: Attitude Change in the Face of an Epidemic.” Social Forces, vol. 84, no. 4, 2006, pp. 2167–2178. JSTOR

Sered, Susan. “Why 'Waging War' on Coronavirus Is a Dangerous Metaphor.”

“Signs and Symptoms.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2 Feb. 2023.

Sontag, Susan. AIDS and Its Metaphors. Penguin, 1988.

“The ‘Homosexual Cancer’: AIDS = Gay.” Movement, Knowledge, Emotion: Gay Activism and HIV/AIDS in Australia, by Jennifer Power, ANU Press, 2011, pp. 31–58

Variants of the Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022.

“WHO Recommends New Name for Monkeypox Disease.” World Health Organization, 2022.